Why I left the United States: My Life in Germany

I left New York City to study and live in Germany. This is my story and the ultimate start of the CCT Method.

"You go and live your life, dear. And if you don't want to, don't ever come back."

These were the words my aunt told me as she left me at the gate on October 5th, 2017 when I left everything and everyone that had ever been familiar to me and permanently move (back) to Germany.

What followed were the five most transitional and transformative years of my life.

In some ways, these five years have felt like fifty both in depth and breadth. I've learned an enormous amount about culture, science, history, business, other people but most importantly - myself. I only just now have started having the time to tell my story and share this wild ride.

So if you're curious how a skinny nerd from Queens, New York left one of the biggest cities in the world to find his heart and fortune in a small (but thriving) German city, read on.

"You can only connect the dots looking backwards" - Steve Jobs

But Why Germany?

The seed of my motivation to move to Germany began in 2010-2011 when I did my exchange year. I was studying dual degrees in Psychology and German. I excelled enough in German where I got a few scholarships and was encouraged to do the year abroad after having done a six-week intensive course abroad in the same city.

I had no money for university so I was riding on student loans and had never been given money to go anywhere, let alone study. A scholarship to go to Europe sounded like the adventure of a lifetime. It was.

Pictures from my exchange year in Leipzig, 2010-2011

I studied (hard) because yes, studying abroad is fun but it's not a vacation.

Ate (a lot) because yes, the food is better. Period.

And drank (even more) because...German Beer.

All while still managing to jump to near fluent German level (C1) in just over a year so,...not bad.

I met my best friend and plenty of others who remain friends to this day.

But studying in Germany also opened me up to very stark differences between the way things were there and in the U.S., specifically the stark differences in three areas:

- Healthcare

- Access to education

- Quality of Life

And while each one of these topics is enough for an article on its own, I'll quickly summarize why these points became deciding factors for my move.

Healthcare

Germany has universal healthcare meaning it is heavily subsidized by the state - more accurately, the relatively high taxes. However, in Germany I can see that tax money at work. Something the United States, despite being the "greatest country in the world" still can't seem to get implemented as a basic principle and human right. Oh well, we'll see how that pans out.

While I thankfully spent my year abroad not having to "test" the healthcare system in Germany, I would later find out in June of 2022 when I fractured my arm.

I was riding my bike home one evening after a heavy rain when I wiped out just down the street from my apartment. I landed on my elbow and my face/head followed. My helmet probably saved my life. I proceeded to the hospital where I received:

- Two x-rays

- CT Scan to check for a concussion

- A sling and

- Two pain-killer prescriptions

All of which came out to a whopping 14€...with the co-pay for the painkillers.

Weeks later I called two close friends who are physicians back in the US, explained what had happened to me and asked how much the same situation would have cost me there. They answered that "depending on the insurance" it could have cost anywhere between $1,200 - $3,500.

Given the fact that that is what most rents or even a mortgage can cost, Germany can take my money.

Moreover, Germany's laws protect the existence of both brand-name and generic medical brands, making most of the essential medications accessible at all price brackets.

Access to Education

While in Germany back in 2010, I made a few friends who were studying medicine. They were ambitious, clever, and hilarious. Our conversations could go on for hours. At the time, I was about half way through my psychology degree and had already started assisting in graduate research with a strong neuro-biological component. This made great fuel for the conversations with my medical counterparts.

Eventually one of them said: "The lectures are open to all students. You should come to a few." And that's exactly what I did. In Germany, all students (regardless of faculty) pay one tuition fee. While there are plenty of private schools in Germany as well, all educational institutions are heavily subsidized according to state and their tuition fees reflect this fact.

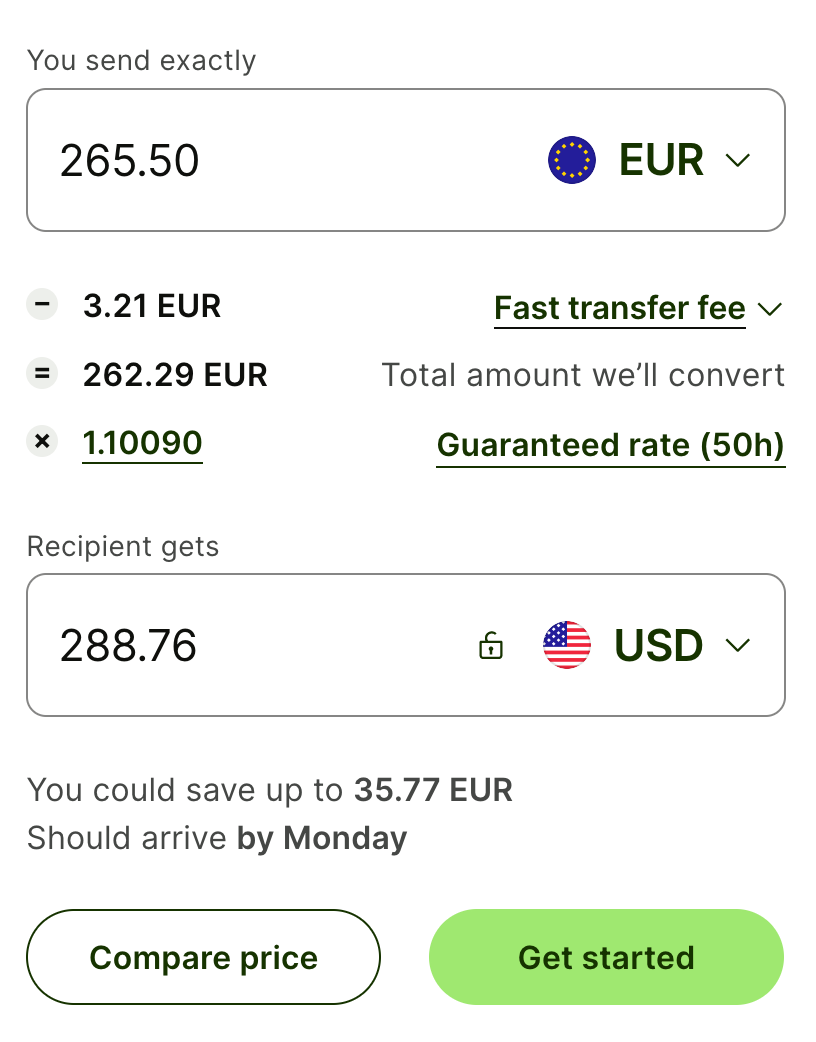

(At the time of writing this article - Currency conversion with Wise.com)

I took my new friends up on their offer and followed them to lectures on anatomy, physiology, and pathology. That was enough and I was hooked. By the middle of summer semester in 2011, I began entertaining the possibility that I might return to the US, graduate, and then apply to medical school in Germany to get a world-class education at a fraction of the price. Given the fact that I had already taken well over $20,000 in loans and had nearly mastered the German language, you can see where this became a very attractive option.

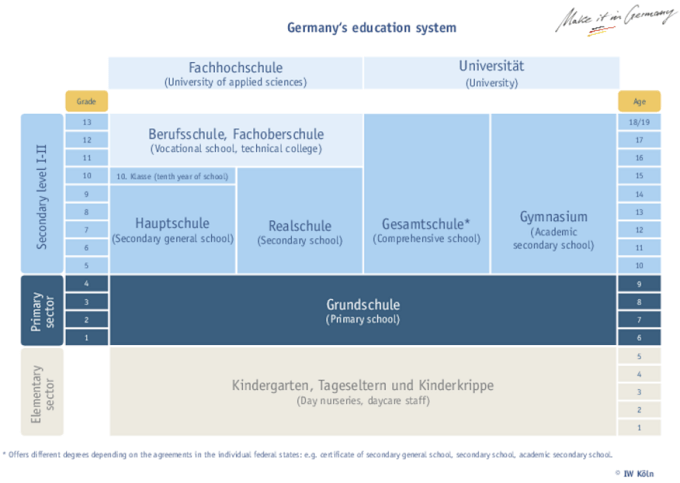

While not without it's flaws, the German education does a very good job of what I will call "vocational orientation". By this I mean that the system begins aptitude tests quite early and the society is already ''split up" according to skills and aptitude by the time students reach high school.

Standardized testing begins in primary school. Students are then placed into one of the four different kinds of High School systems. Each system then continues to test and track aptitudes which presumably place students "on track" for either Trade School, University of Applied Science, and University. Unlike US Americans, Germans are not told they can "be anything they want to be"; rather they are encouraged to pursue things they excel at from an early age and see it all the way through to specialization. All students take a test called an "Abitur" which ultimately determines their to which form of higher education they are eligible. Think like the SAT but on steroids. Fun (not). This specialization is both the strength and curse of the German system which is a topic for another article.

While this might seem rather limiting to some, it has (for better or worse) worked very well here and the economy enjoys one of the lowest levels of unemployment in the world.

So again, Germany can have my money.

Quality of Life

With all it's imperfections (and there are plenty), Germans still enjoy one of the highest quality of life in the world.

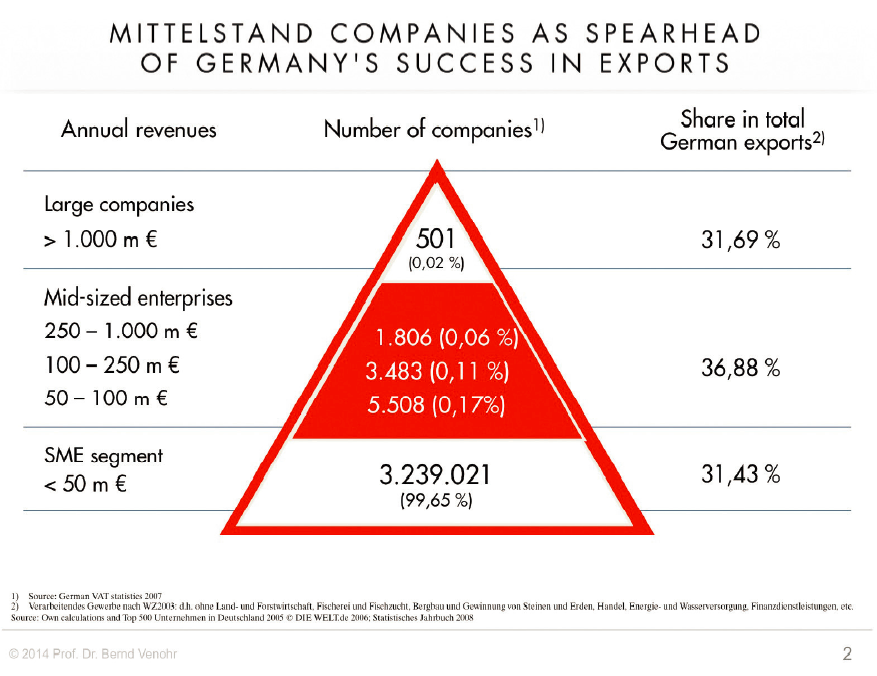

Germany boasts one of the strongest and wealthiest middle classes in the western world. Most industries are highly unionized and employ an enormous amount of the population which in turn provide for the sustained tax revenue and you can see where this stability translates into other areas of the economy and life. One of my own cousins lives and works near Frankfurt and enjoys a very comfortable lifestyle working on a factory floor for a major automotive company.

While economists have not precisely defined the term "mittlestand" or "middle class"; it is clear that compared to it's American counterpart, Germany's middle class is alive and well. This is also reflected in the proverbial German work-life balance as encapsulated in the following saying.

"Freitag um eins, macht jeder seins." - common German saying

"Friday at 1, everyone does their own thing". In other words "all work and no play makes Hans a dull boy."

Contrary to popular belief, most Germans work to live, not the other way around. Work is seen as a means for then later doing what you truly enjoy after work and on the weekends. While it obviously depends on who you speak to, Germans do well to not identify with their work in the way US Americans tend to. Moreover, it can even be considered rude to talk about work in social settings unless it is directly relevant.

Time off - Most full-time jobs come with 20-24 days off per year with the opportunity to increase that by a few days after a few years. Moreover, these don't include the many bank and religious holidays. Germans take their time off very seriously. Also, most work environments are understanding when employees take one to two days for recovery due to sudden illness or a mental health day; however after the third day of being sick, you are required to get a doctor's note if you would like to get paid for that day or need more time to recover.

After living among these people wh0 (assisted by the US no less) had come out of the rubble of a world war, survived a soviet-communist regime, and cultivated one of the most robust economies and multi-party functioning democracy in the western hemisphere; all the while providing socially accessible benefits (without imploding) I could not reasonably return to the US and see it the same way again.

Summer 2011

I returned to the US in the summer of 2011 determined to wrap up my studies and apply to medical school in Germany. And while it weighed heavily on me that I would leave my McNair Scholarship program on the table, I felt Germany was just a more level playing field for a young ambitious guy like me with limited means.

And while my ambitions were eventually realized, they were not to pass as I imagined them.

A Turn of the Tide

By the summer of 2011 I had completed all of my degree requirements with all but one class - Statistics.

Math was never my forte. And while I was usually able to understand conceptually what was going on, when it came down to the grind stone I frequently found myself lost in the sauce. Moreover, I suffered enormous test anxiety and was barely able to overcome it for other subjects I enjoyed!

Despite my interest in it, statistics had haunted me for the entire duration of my studies as the subject I failed twice (at my home university) and a third time at a neighboring university before I ultimately passed it at a local community college.

I was supposed to graduate in 2012 but was prohibited from doing so when I failed statistics the second time at my home university. That spun me into a very difficult five years of my life where I worked a series of jobs ranging from baby-sitting to waiting tables, and eventually to printed/digital media, finance, and marketing before I decided to return to crush statistics and graduate.

Over the Pond

With my Bachelors degree now in hand, my ambitions of moving back to Germany and pursing a world-class education at a reasonable rate that I could work off as I studied was now within my grasps. Or so I thought.

On October 5th of 2017, having packed my life into an army-duffel, a single carry on, and a backpack, I boarded a flight out of Newark Airport, New Jersey with a one-way ticket to Germany. My goals were clear: (1)Find a job, (2) Work and save for a year to start with a financial cushion, (3) Apply to Med-School (4) Become a German-accredited physician (5) Become a German citizen. (6) Look back only once everything was said and done.

I arrived and stayed with friends - a friend I had made back in 2010 and her husband. They welcomed me very warmly and I stayed in the spare room of their bungalow at the city's edge.

I quickly set out looking for work and found it working in sales at an e-commerce company. Despite my own background in sales and marketing, this job in particular was not the right fit and the employer and myself decided to terminate the relationship after about six weeks.

Panic began as the rent for the apartment I had found (which I had signed a year lease for) was coming up and I still found myself without work nearly a month after leaving the company.

Thankfully, just shy of a month after, I found a job listing for a research assistant at the prestigious Max Planck Institute (MPI) for Evolutionary Anthropology.

And while the job mainly consistent of archival work for a student doing her PhD in conservation studies, it afforded me the chance of a lifetime to interact with some of the top minds in fields that included: evolution, archaeology, anthropology, primatology, and molecular biology just to name a few. For someone like me with a heart stuck somewhere between the arts and sciences, this "happy accident" was a dream and a welcome opportunity. I even briefly met a researcher who would win the Nobel Prize just years later!

My rent was depleting my savings (fast) but at least I had another stepping stone and was already building my CV in Germany. What followed was probably one of the busiest summers of my life. My position at the MPI was only part-time and so I resorted to waiting tables and English tutoring as well. I had three jobs that summer and while looking back now it was pure madness, I can safely say it certainly built some character.

It was around this time that I learned my grades were just shy of what German medical faculties typically accept. But if I'm completely honest with myself, I had begun second-guessing the whole thing anyways. I had only heard horror stories of the quality of life physicians frequently faced and my life was hard enough running around trying to eat and make rent. I was not keen to start med-school in that condition. I made the decision to withdraw my application and find some steady ground first.

I would never go on to study medicine. But I know now that was probably the best thing that could have happened. If you read on, I think you'll see why.

The Law of Surprise

Within weeks of getting here I had met a young Russian/American couple at a networking event and we kept in touch. I mentioned in passing during one of our meetings that I was looking for more consistent work and she said the company she worked for was consistently looking for new hires.

"Have you heard of Wirecard?" she asked.

While the position was an entry level customer service job, Wirecard was a German stock market (DAX) darling. It was a financial transaction processing company that had strategically positioned itself in the market and projected itself as the technological and Fin-tech innovator of the decade. I just saw the steady paycheck and an opportunity to get onto more stable ground.

You can imagine my surprise then in 2019 right before the pandemic when the headlines hit that 1,9 Billion euros had "gone missing" in one of Wirecard's foreign accounts and that their chief operations officer had run away to Russia.

In short, the German Federal Financial Regulators (BAFIN) had fallen asleep at the wheel along with auditors Ernst and Young (EY) and "neglected" Wirecard's intricate (shady) web-like corporate structure which ultimately could not account for the money.

The company stock went into free-fall over night, insolvency was declared, and the company was sold off in pieces while thousands were fired or laid off and the company's C-level wrote dissociated encouragement emails to their panic-stricken workforce from their yachts in Mallorca.

Employees in my branch were given the option to stay and "take a chance" on the company's survival or accept a severance package totaling two months pay. Fortuantely, I had been planning to leave the company for months anyway and begun looking elsewhere. I found a job as an entry-level business researcher at a small venture capital firm, took my severance from Wirecard, and never looked back.

New Ventures

I happily left Wirecard but not without getting a tip that would lead me to exactly here and now. Our job could get quite monotonous but most of the workforce were people just like me: immigrants with credentials just trying to make it work in this new world of sausage and sauerkraut.

I spoke very often to a colleague of mine who at the time was graduating from an MBA program. Once it was clear that Wirecard's days were numbered, he pulled me aside one day and asked:

"You're always talking about all these ideas. Ever think about going to business school and learning how to make money out of them?"

That singular question set my life on the trajectory to today.

I applied to the program in spring of 2020 for the fall/winter semester of that year. The rest as we know is history. While accepted to the program, most of it was entirely online as the world (and Germany in particular) went into lock-down; pushing all our economic and psychological stability to the breaking point.

Work at the VC firm went on as usual. The team made adjustments for working remotely at the slightest cough or scratchy throat so we would all be as safe as possible. It made my on-boarding a bit haphazard but it was crazy times for all of us. I'm sure most of your can relate.

The VC work was both everything I expected it to be and not. A break-neck speed environment spending hours going into the weeds researching technologies at the frontiers of science, days reading, interpreting, and preparing presentations, talking with decision-making level clients. It was intense but exhilarating. A welcome change from the monotony of a customer service job at a dubious company making minimum wage.

Back in 2019, while doing a Master's in Bioinformatics (which I ended up withdrawing from), I came across Vertical Farming (VF). I was researching areas in technology where the jobs would be by the time I graduated, and VF was definitely one of those areas.

I came across The Association for Veritcal Farming, a platform which served to connect actors and stakeholders in the field. They were hosting a conference in Oslo, Norway so I scraped what little money I had together at the time and took a leap. What followed was a nearly three-year long obsession with agriculture, food, and AgTech.

I returned to Leipzig and began speaking with everyone I knew about VF like an evangelist. In retrospect, it must have been very annoying. But word got out. And one day I heard from a colleague that one of the companies in the VC startup portfolio was a VF company. I requested a meeting with the co-founders and heard back a week later that I'd gotten the job. The VC firm was sad to see me go from the day-to-day activities but they knew if the startups were well-staffed, it would be a win-win for everyone, so they happily let me go.

My time in AgTech (2020-2022) - One of my many functions was seeding, plant care, and experimentation.

A Change in the Winds

There is no price on experience. I learned more about business in those two years of working in a startup than can ever be taught in any theory books about business, hr, product development, design, marketing, and leadership just to name a few. Some of the best lessons were lessons about people.

I learned first hand the truth behind the saying that frequently the people who start a startup are not the ones to scale it. After a few years, team dynamics began to change as did values and desired directions. I did grad-school all the while working 20 hours a week at the startup, but as the research and writing portion of my studies approached, I decided I needed something a bit more stable. The last thing I wanted was to show up to the immigration office to collect social benefits if the startup went belly up while still finishing grad school.

I decided to start looking. One day, as if out of a film, I ran into a former colleague in the town square who told me her work was hiring. I went over the same day, met the hiring manager, applied, went in for an interview, and was hired a month later.

I left the AgTech world older, wiser, and with an enormous sense of accomplishment and gratitude.

What Now?

That brings us to the present day.

By the time you read this, I'll have completed my thesis, graduated, and be preparing to launch not one, not two, but three businesses.

This is not intended to be a flex. I merely want to show what is possible to anyone who might be feeling lost, hungry for more and knows there is something better out there for them than what they are presently living.

In 5 years I moved to a foreign country with just a few thousand dollars in savings and gift money, squeezed every euro cent from that, found my way, and found a graduate school program for a fraction of the cost that it would cost me in the U.S. I'm am finishing with hardly any debt, and can immediately start making anywhere between 60-80k a year in salary or even more through freelance services.

I'll apply to German citizenship in the coming months and have free range to work from Olso to Naples; Lisbon to Bucharest. All because I chose a different path.

"Before you save the world, make sure your own house is in order." - Charles F. Glassman

I developed the CCT Method out of necessity. Firstly to put my own house in order and now to help others do the same. It is the aggregate result of my burning curiosity to explore the depths of the human condition and live the highest quality of life possible.

In my heart, I am stuck somewhere between a scientist and a poet, but I've somehow made it work. I do not pretend to know everything. In fact, I've become completely comfortable with that state of not knowing. The state of awe and wonder; of magic and mystery.

The only thing I know for sure is that my curiosity is insatiable and that alone is enough to carry me anywhere.